17 Jul Soup Kitchens and the Great Hunger.

Soup kitchens

The great hunger.

There had been Famines before it and Famines after it. Without a doubt, the worse was the Great Irish Famine 1846-1851. This period especially 1846 and 1847 was affected by Government propaganda and revisionist and national historians and much of what they wrote have been compounded by extant historians.

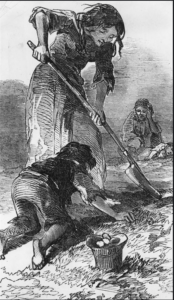

The winter of 1846 was one of the worst in Ireland for growing potatoes [potatoes and bread was the stable diet for the Irish rural and poor population]. Potatoes were either rotting in the ground [it was estimated that nine million potatoes were rotting] or suffered ‘potato blight’. At the start, there was plenty of National responsibility by the English population, but this changed with the election of the laissez-faire Whig government in 1847. Prior to that, the conservative government of Sir Robert Peel accepted the responsibility of feeding the poor of Ireland. Doing this through the Poor Act and giving outdoor relief.

The main relief was cornmeal, although the Government was importing corn and maize and selling it at the market price cornmeal’s were very unpopular with the Irish poor claiming relief. On the 24th March 1847, the United Kingdom held a national day of fasting and humiliation. This was marked by a general stoppage of work in shops and businesses, the churches opened and general collections for the poor and hungry of Ireland was established. However, the Metropolitan poor viewed that day as a day of fun. The fast day and support for the Irish proved very ephemeral and could be one of the reasons why in the UK on 24th March 1847 General Election Peel’s Tory party lost and the Whig’s Laissez-Faire Party under Sir John Russel gained the day, which will affect the poor in Ireland in a very big way.

The Whig government put in place Charles Trevelyan to oversee the Irish Famine quickly decided to stop importing corn and maize, thereby stopping cornmeals. They also decided that they should end ‘outdoor relief’ and encourage the use of local workhouses. [Remember it was a previous Whig government that bought in The New Poor Act in 1834]. Trevelyan favourite saying, “The Judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson that calamity must not be migrated”. To the Whig government, it was a matter of costs and they intended to reduce them. They had already decided that the Irish poor should be given ‘free soup’ through soup-kitchens which were to be funded by generous benefactors. They expected wealthy landowners to donate to the government through ‘poor law rate’. Before 1838 when it was parochial rates. Although they grumbled, they tended to pay them. However, when parishes were gathered together to form unions, they objected in stating there was not enough land or property owners to pay the poor law rates. Trevelyan thought soup-kitchens was the cheapest way to deal with the famine. Therefore, the Government brought out the 1847 Soup Kitchen Act

Enter Alexis Soyer.

Soyer had designed a soup-kitchen which he had called Soyer’s Parochial Kitchen and had one installed in Bethnal Green and Spitalfields. His mentor the duchess of Sutherland knew about his soup kitchens and asked him to meet Lord Bessborough, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. On meeting Bessborough who then asked Alexis if he would take his design to Dublin Ireland and show people how a soup kitchen worked. Alexis agreed but needed permission from the Reform Club who at first gave him permission for 4 weeks and then allowed a further 2 weeks extension. With his soup kitchens in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green, Alexis had felt that the soup that was being given out was not so much soup for the poor but poor soup for the poor. Alexis had then put his mind to creating some beneficial soup for the poor which he practised on Reform Club Members and most approved the soup. Alexis thought he would be able to bring these soup receipts with him. Alexis’ soups cost ¾d a quart to make however he was quickly informed that he could not use his receipt’s as they were too costly. Even before he got to Ireland his there were complaints about his soups. Prior to Alexis even going to Ireland and setting up a soup kitchen, an article appeared in The Lancet. It accused Alexis of ‘soup-quackery’. It appears that somehow Alexis had upset someone. The article in The Lancet was written by an unnamed author, who was taking issue with Alexis’ claim that: “A bellyful of my soup, once a day, together with a biscuit, will be more than sufficient to sustain the strength of a strong and healthy man”. Alexis had devised some Famine Soups and was trying them at the Reform Club; his critic must have tasted the soups there – leading one to suppose that he must have been a Reform Club member. On arriving in Dublin, he heard mumblings about his soup This was the first time – other than from the odd Reform Club member – that Alexis faced criticism. The critics seemed to resent a chef from a rich man’s club coming to oversee the soup kitchens for the poor.

For Alexis, the criticism had to be stopped, or the whole venture would be a failure. A suggestion came from the small band of critics – that the Famine soups should be tested by an independent nutritionist. One was appointed by The Royal Dublin Society, his name was John Aldridge, who was a Professor of Chemistry. He based his report – which was very long and wordy – first on animals that eat vegetables. How much they ate and how much they wasted through body-waste and what weight loss, if any, took place. He then transposed these figures to a human being and worked out what a four stone child would need in nourishment to remain the same weight. On testing Alexis’ soups on May 6th, 1847, he readily agreed with Alexis that the fact his soups contained all the vegetable including any leaf or topping, added important nutrients to the diet. Alexis showed Aldridge how he had considered the extra needs of children and planned to give them beef soup, pea panada and rice curry. Aldridge, who partook of the pea panada, though it was extremely palatable and very nutritious – he personally felt that it would benefit with some onions.

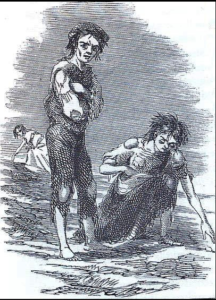

Boy and girl looking for potatoes in Ireland 1847

Aldridge tested other soups besides Alexis’ but admitted that all Alexis’ soups would help a man keep alive for quite some time. (It must be remembered that the ‘normal’ diet of the Irish poor was potatoes, bread and water.) Aldridge claimed the most nutritious and cheapest soup was Soyer Fish soup No 6-famine soup. He also added: “In the name of the Irish people I thank M. Soyer for what I believe to be his purely philanthropic intentions towards them. He has given to us two boons of no ordinary value, a model dispensing kitchen of great ingenuity, and a method of economic cooking far superior to any to which the poorer order of out countrymen has hitherto been accustomed”. Alexis proclaimed through local Irish papers that indeed his soup was nourishing, it would not replace the main meal, but people could survive with just his soup and they could do so for several weeks. This seemed to stop all the critics in one fell swoop. He challenged anyone who could do better to do so. There were no takers.

Several Irish historians recant about Soyer his soup kitchen and his bad soup in doing this they always reference a book The History of the Great Irish Famine of 1847 by John O’Rourke who had written about people complaining about Soyer’s soups, But he did not write about Alexis demanding that his soups were to be tested. Historians needed to read Paddy’s Lament by Thomas Gallagher to learn about prof’ Aldridge testing Alexis’ soups

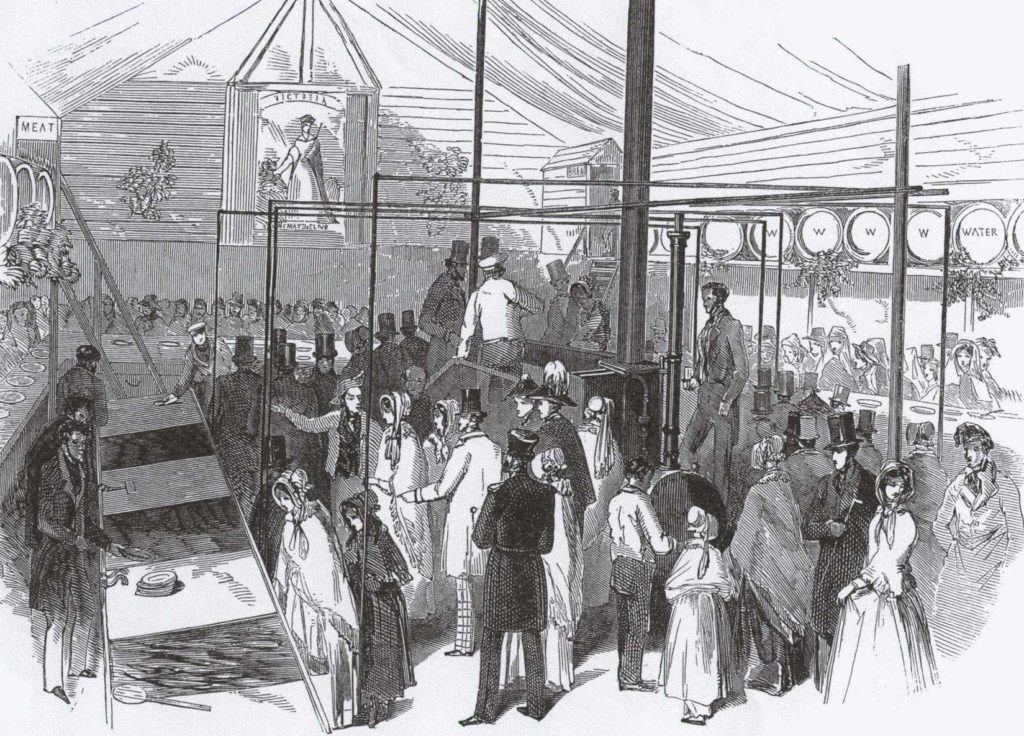

Finally, the Soup kitchen was completed in The Royal Barracks Esplanade, Dublin and on the 4th April 1847, it was opened to the public. George, Prince of Cambridge, came and was very impressed and tried some of Soyer’s soup. I have come across several descriptions of the kitchen. The one I prefer is the following that Alexis told to The Illustrated London News:

“The exterior and covering are of a temporary nature, being formed of boards and canvass, enclosing a space of forty-five feet long, and forty feet wide. The interior consists of a steam-boiler, on wheels, thirteen feet long, and four feet wide, with a glaze-pan over it, capable of containing three hundred gallons; and at the end an oven to bake one hundredweight of bread at a time; and all heated by the same fire. Under the boiler is an excavation to contain coals and round it an elevated platform to give access to the glaze-pan. At the distance of eight feet, round the boiler, are eight iron bain marie pans with covers, six feet long and twenty-two inches wide, on wheels, and made double, to be boiled, by steam, and contain, together, one thousand gallons. At each end, extending between the pans, are the cutting tables – at one end the meat, and at the other, the vegetables; and under which are placed wooden soaking tubs, on wheels, and chopping blocks for the meat drawers and sliding shelf. Four feet beyond these are placed a row of tables, eighteen inches wide, in which a hole is cut, and therein placed a quart iron white enamelled basin, with a metal spoon attached thereto by a neat chain; there are one hundred of these, and the table forms the outer boundary of the kitchen; leaving a space of two feet six inches between it and the wall. Inside the table are fastened tin water-cases, at the distance of ten feet apart, containing a sponge &c, to clean out the soup basins.

Round the two supports of the roof are circular tin boxes for the condiments. Seven feet from the ground at each corner is placed a safe five feet square and seven feet high, with sides of the wire, for ventilation, which contains, respectively, meat, vegetables, grain and condiments. At the same elevation as the safes are sixteen butts, containing 1792 gallons of water.

At the entrance in the centre, is the weighing machine. The fire being lighted, a certain quantity of fat or dripping is placed in the glaze-pan, and in the soup-pans the farinaceous ingredients, or thickening, along with the water. As soon as the fat is melted in the glaze-pan, the vegetables, cut into thin slices, or dice, are placed therein; after the lapse of ten minutes, the meat, which has been previously cut into small pieces, is added, and allowed gradually to fry, until the juice is extracted, and a good glaze formed, which will be in about thirty-five minutes.

The condiments are then added, and the glaze is removed and distributed equally in the bain marie pans; it is boiled for twenty minutes, and the soup or food is complete; this is the time used in making the soup, when such farinaceous ingredients or flour, oatmeal, and rice or barley, previously soaked, are employed; but peas, Indian corn meal, and many other ingredients, will take longer boiling. It is ready to be removed by ladies into the basins in the surrounding tables. Outside the table is a zigzag passage capable of containing one hundred persons in a small place in the open air; at the entrance is a checker-clerk, and an indicator; or machine which numbers every person that passes; and on the other side is a bread and biscuit room, where those who have partaken of the soup, and are departing, receive on passing a quarter of a pound of bread or savoury biscuit; as I prefer giving it then, instead of with the soup or food, it being sufficient for one meal without, and will not only save time, but when eaten afterwards, will be more wholesome, and act more generously on the system, than when eaten in haste. When the soup or food is ready, notice is given by ringing the bell, and the one hundred people are admitted and take their places at the table – the basins, being previously filled, grace is said – the bell is again rang for them to begin, and a sufficient time is allowed them to eat their quart of food. During the time they are emptying their basins the outside passage is again filling; as soon as they are done, and are going out at the other side, the basin and spoon are cleaned, and again filled; the bell rings, and a fresh number admitted; this continuing every successive six minutes, feeding one thousand persons every hour; but as there are three thousand quarts more to distribute, which occupies only seventy minutes to make, other means must be used for distributing the food for which purpose a door is provided at the entrance of the kitchen, to which persons come with tickets, which are given to them by district visitors or subscribers; or, if not with tickets, to purchase the food, and which they take home with them. There are also provided carts and barrows for either horse, donkeys, or men to draw, containing from twenty-five gallons to two hundred gallons each, with fires attached, so that the soup or food contained in them should be hot or cooking on its way to the place of distribution. Such is a brief description of the kitchen. I also propose to change the diet every day, according to the provisions obtainable, and on fast days to give meagre food.

It cannot be stressed enough how important Alexis’ kitchen was for Ireland, allowing many more people to be fed. His kitchen in some semblance or other was copied in most towns. It did not resolve the politics of Ireland, nor cure the potato famine but it did save lives. Alexis already mentioned the benefits that besides serving soup it could distribute it as well, allowing small villages and obscure houses to benefit from the soup. Of the people who complained about the soup, not one was in need or even partook of the soup. Those that did, the poor, were grateful for the soup and that is all Alexis cared about. However, the poverty that Alexis saw had a great effect on him.

Alexis left Ireland on Sunday 11th April 1847 and on the night before; several of his friends gave a dinner in his honour, at the Freemason’s Hall, College Green. He was thanked for all that he had done for Ireland. He was presented with a very elegant snuffbox, with the inscription. “Presented to M. Alexis Soyer, in testimony of the high sense entertained of his valuable scientific and philanthropic services while engaged in this country on his mission of good in behalf of the destitute poor, by some of his admiring friends, who gladly avail themselves of an early opportunity to mark their regard for himself personally, and the esteem in which his beneficent and truly useful labours have been held by them, Dublin, 10th April 1847.” On the 10th April 1847, the Model Kitchen was handed over to the ladies of the South Union Relief Committee of Dublin, who ran it very successfully until the end of autumn when all soup kitchens in Ireland were closed, although the need for them was still required in 1848. The British Government in its infinite wisdom decided not to open them again. They considered the soup kitchens as outdoor relief which they were trying to stop, they felt the poor should go into workhouses.

However, after Alexis left Ireland people started to complain about his style of soup kitchens. Such as plates and cutlery being nailed to the tables. How they only had about 4 minutes to eat their food. How they had to join long queues and then being allowed in the soup kitchens, a certain amount of people. They simply felt their dignity and pride was taken away from them. Also, there is a word that most present-day Irish hate and that is “Souperism”. Quite a few soup kitchens were run by the Protestant church and organisations and they would refuse to give the Catholic poor any soup unless they proselytise to the protestant faith. The Catholic poor became very weary protestant do-gooders and would seek help elsewhere. Souperism helped the government close all the soup kitchens, up to the end of July outdoor relief was costing the government £3,020,712 per month by closing the soup-kitchens spending on relief was £505,984. It is estimated that a million people died during the Great Famine, that two million people emigrated leaving an Irish population of some five million people.

In my research of the daily newspapers during Alexis’ time in Ireland, they were all very supportive The Cork Examiner in an article in 1848, summarising the effects of the famine on Ireland to date, pointed out that 340 doctors had died through starvation. They also credited Alexis Soyer with saving hundreds of lives, with his Famine Soups.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.