10 Sep It’s Saucy, it’s a Gas. He is an Author of Books and was an Inventor as Well.

It’s Saucy, it’s a Gas, He is an Author of Books and was an Inventor as Well.

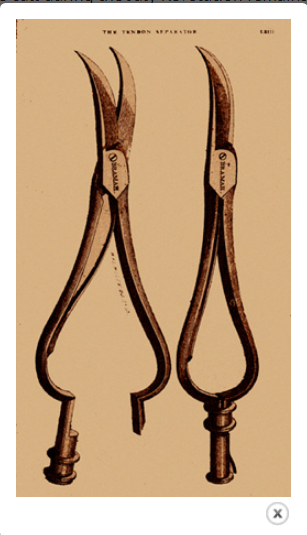

Soyer’s Tendon Separator.

Alexis Soyer was a very multitalented man, some including myself would say he was a polymath if he had a fault it was that he trusted people too much. He was often taken advantage of and he suffered for that. It is remarkable with very little education, what he achieved. He could not read or write English in his early days of being in England. His skill was to become a grandmaster of cooking, publish several books, made several commercial sauces, helped the financial well-being of companies such as William Clayton & Co and Crosse & Blackwell. He had several inventions to his name and saved hundreds of lives with his philanthropic works in Ireland, London and the Crimea.

Alexis Soyer was a man whose decisions were difficult to understand at times. I can give you an example on the 8th May 1850 (the same time as disclosed to the world his Soyer’s Magic Stove) he submitted a design for the Great Exhibition 0f 1851, his design incorporated Marble Arch as the entryway. On 30th December 1850, he paid £600 for the lease of Gore House for 6 months coinciding with the building and open times of the Great Exhibition. Therefore it is confusing how he would manage to fit all these projects in.

Books.

- Delassiments Culinaire. Publisher W. Jeff, 1845.

- Culinary Relaxation. Publisher Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1845.

- Gastronomic Regenerator. Publisher Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1846.

- Charitable Cookery or The Poor Man’s Regenerator. Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1848.

- The Modern Housewife or Mènagé Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1849.

- “Modern Banquets’ found in The Pantropheon by Alphonse Duhart-Fauvert. Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1853.

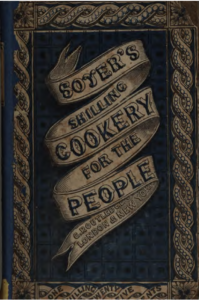

- Shilling Cookery for the People. Published George Routledge & Co. 1855

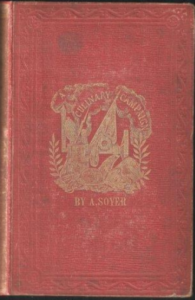

- Culinary Campaign. Published George Routledge & Co

- Instructions for Military Hospital Cooks in the Preparation of Diets for Sick Soldiers. Written with George Warriner. Published Stationery Press. 1860.

It was always thought that Alexis’ first book Délassements Culinaires which was published in 1845 although not a cookery book, was written and published in French. It was a strange book, included in it were small novelettes, La Fille de l’Orage – Revue Seria Buffa – Le Mystére des Coulisses de Theatre de Sa Majesté – Tribulation Domestique – La Rêve d’un Gourmet – Le Plat d’entrée Pagodatique – La Crème de la Grande Bretagne. The La Fille de l’Orage was written for Fanny Cerrito. It is debatable whether it was ever performed and the La Crème de la Grande Bretagne was for female nobility and was a homage to the Duchess of Sutherland

Soyer’s Shilling Cookery for the people (American Version)

But we have a strong case of befuddlement, according to the newspaper ‘Lloyds Weekly 28th November 1845’, there is an article about a book by Alexis Soyer called ‘Culinary Relaxation’. Then we have another paper ‘The Era 7th September 1845. They carried an article headed ‘Culinary Relaxations or Délassements Culinaires’ implying it is the same book. There are several newspaper articles claiming the title is Culinary Relaxations. On further research, it appears that Victorian publishing houses would sometimes have a different title for London than the rest of the nation. I don’t think either title did well because with the first to the fourth edition of the Gastronomic Regenerator they carried chapters La Fille de l’Orage and The Cream of Great Britain

In 1853 a book called The Pantropheon was published under Soyer’s name. The author of this book had to be aware of Roman and Greek Classical History of food and understand Latin and Greek, this was certainly not Alexis Soyer. Alexis’ father died in 1818 and less than a year later, his mother Marie Chamberland married Pierre Travets and moved to Crecy-la -Chapelle, France, if Alexis did go to school it would only have been for a couple of years. As far as Soyer historians are concerned the accredited author was a French Language Teacher called Adolphe Duhart-Fauvert It was a detailed and scholastic study of the cooking methods of the Roman and Greek empires. On the title page found in a copy of The Pantropheon, written in French, is a dedication to “Pauline Duhart-Fauvet from the author, her husband, with tender devotion”, signed Adolphe Duhart-Fauvet and dated 3rd September 1853. Below this is a statement saying that he never agreed when selling his French Manuscript and that the name Soyer could be used alone. Again, above the heading ‘Modern Banquets’ he had written that Alexis had added this chapter without his permission. Duhart-Fauvet never took Alexis to Court. It could well be that he acted as a ghost-writer for Alexis and changed his mind, Alexis promoted the book in about 50 newspapers in 1853. There is also another suggestion. In 1851 Alexis opened a very large restaurant in

Soyer’s Culinary Campaign.

London, to run it, it simply burnt money. It went bust and he closed the doors to the public on 14th October he was in debt by about £7,000, which in 2019 money was £561,302 a lot of money. In 1853/4 a man called David Hart who was in partnership with a George White were partners in his father’s business Lemon Hart Rum & Son. In the London Gazette, it showed that they were major creditors for several businesses and they made a deal to cover Alexis debts. This was not a benevolent offer, for the 8 years before he died in 1858, any money Alexis earnt he had to pay his creditors David Hart and White. When Alexis died his estate was only worth some £1,500 and his will was annexed by Hart & White. Therefore, another suggestion is that Hart & White made some sort of deal with Dahart-Fauvet, then forced Alexis to claim he was the author. In 1854 there was a court case about The Pantropheon Holson V Abbott & Barton, the defendants being the promoters of the book. Holson had pre-ordered copies of the book and they had not been delivered. When Alexis was in the witness-box he made an extraordinary statement, he claimed, “The Pantropheon being very much altered now and the book is not of that utility that it was at first.” He further explained “He had hoped to have 5,000 copies ready by the time The Great Exhibition opened 1st May 1851 which he failed, and he then stated he wished he never advertised the book. Could Alexis have been talking about adding ‘Modern Banquets’ as Duhart-Fauvet had accused him of? Unfortunately, it is now only speculation.

Soyer Sauces.

William M Clayton & Co.Watling Street, London

- Soyer’s Diamond Sauce – 1847.

- Soyer’s Versailles Sauce -1848.

- Halo Genesis or Kalos Geusis -1849.

Soyer & Co. Rupert Street London.

- Soyer’s Effervescent Nectar – 1848

- Soyer’s Orange Citrion Lemonade – 1849

- Soyer’s Ginger Beer -1849

- Carbonated Soda Water – 1849.

A. Soyer & Co. Partnership with George Warriner

- Soyer’s Osmazome Food 1850

Crosse & Blackwell Soho Square London.

- Soyer’s Sauce for Gentlemen -1850.

- Soyer’s sauce for Ladies – 1850.

- Soyer’s Relish -1850.

- Soyer’s Aromatic Mustard – 1854.

- Soyer’s Sultana Sauce – 1857.

One of Soyer’s sauces Halos Genesis.

Again, with his Sauces and Beverages, Alexis does not disappoint us with his trips into these businesses. He leaves us confused, amused and baffled. The first time we hear of Kalos Geusis is when a Henry Trinder sent a bottle of the sauce to Alexis Soyer at the Reform Club for a testimonial which Alexis gladly gave – then an advert telling us this was in the 26th May 1849 edition of John Bull. A week later again in John Bull the same advert can be seen but instead of Henry Trinder, it now said William Clayton & Co with the same address as Trinder’s. Then William Clayton & Co was marketing Kalos Geusis, it was even mentioned in ‘The Court Journal’. In a recently published book titled ‘Sauces Reconsidered: Apres Escoffier’ the author admired Alexis’ marketing skills claiming they were ahead of their time, but, thought that the three sauces marketed by William Clayton & Co were badly marketed I totally disagree with that statement by 1849 Kalos Geusis could be brought in Canada, America, New Zealand and Australia. But by 1850, the three sauces disappeared from the marketplace.

Again, about 1848 Alexis was marketing his Soyer’s Effervescent Nectar to much acclaim. The Lancet Medical Journal dated 28th July 1848 approved of it, claiming it was one of the best seltzers that they had tasted it was very well marketed and then added to the list was Soyer’s Orange Citrion Lemonade, Soyer’s Ginger Beer and Soyer’s carbonated Soda water. However, all was not as it seems. Apparently, a company called Carrera Water Manufactory & Co marketed a drink called Tortoni’s Anana but it was very insipid and the drink had not sold, approaches were made for partners in the firm and it acquired two, one bringing in £400 and the other bringing in a £1,000.

Soyer’s Nectar

However, the man who had invented the drink, James Edward Piper suggested to his new partners that they asked Alexis Soyer to become a partner all he had to do was bring his reputation and £100 to become a partner. Alexis was not prepared to put his name to such an insipid drink, so he demanded from Piper the composition of the drink. After much wrangling, Piper gave him the receipt and agreed that Alexis would improve the drink. It would be called Soyer’s Nectar and that the four Partners Piper, Gibbs, Baker and Alexis would be in partnership for seven years and that the company should be called Soyer & Company. Soyer’s Nectar was not the old Tortoni’s Anna, Alexis had completely changed the receipt. it could n’t help Piper’s annoyance when The Sun Newspaper on 13Th July 1848 that Soyer’s Nectar “surpasses all the Lemonade, Iced Soda Water, Sherry Cobler’s and Sherbert and Selzer water we have ever tasted” However, Piper became disillusioned and a creditor had had him imprisoned for a debt from his Carrera’s days. He took his partners and Alexis to the vice-chancellor’s court and asked for the partnership to be dissolved which it was on the 2nd May 1849 and it was listed in the London Gazette on the 5th May. Alexis struggled on with selling his Nectar and not using the name Soyer & Company but in the end, he was advertising and selling paper receipts of his three drinks charging 2/- for each one.

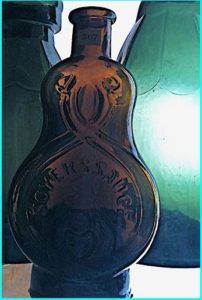

Soyer’s Nectar Bottles

For two years from 1848, Alexis had been marketing two new sauces, Soyer’s Sauce for Gentlemen and Soyer’s Sauce for Ladies using Crosse & Blackwell as sole agent and he was now ready to market his Soyer’s Relish. But they had seen the problems he had with William Clayton & Co, also the problems he had over Soyer’s Nectar. But they also noticed Soyer became restless and bored quickly with his inventions and books. Edmund Crosse and Thomas Blackwell were fast becoming firm friends with Alexis and his sauces were becoming one of their stable and best sellers. They decided to tie Alexis down to a signed contract/debenture so on 22nd August 1850 they asked Alexis to sign a ‘Deed of Indenture’. They brought the licenses of Soyer’s Sauces marketed by William Clayton then discontinued them straight away hence why you could not buy the three sauces in 1850. They insisted that all of his sauces must be at least ½ pint. That they all had printed labels with Soyer’s image, they had actually brought Emma Soyer’s painting of Alexis some months previously. That any new sauces that Alexis would develop would be offered to Crosse & Blackwell first. That he must sign certificates for each sauce disclosing the composition of each sauce to Crosse & Blackwell. That he will not discuss his sauces with anyone else, other than Crosse & Blackwell. For Soyer’s Sauce for Gentlemen and Soyer’s Sauce for Ladies. Alexis would supply the labels and for every dozen bottle of sauce that was sold – he will receive 4/-. For Relish it was less he would receive 1/- for every dozen ½ pint bottles that were sold. Crosse & Blackwell would take on all other expenses such as making, bottling (having bottles made). They would pay £50 per annum for each sauce, advertising them in the daily and leading newspaper. Then added to the stable over the next few years would be Soyer’s Aromatic Mustard in 1854 and Soyer’s Sultana Sauce in 1857. From 1857 the marketing of Alexis’ sauces was very sparse there was no increase in marketing of his products in the year of his death in 1858. But strangely there was a plethora of Crosse & Blackwell adverts and all of Alexis sauces in the 1860 newspapers. Thereafter no more Crosse & Blackwell ads with Soyer’s sauces. Other than in 1865 during the months of May/June, a shop in Sheffield called J. J. G. Tuckwells was selling Soyer’s Relish sauce for 1/- per bottle.

Soyer’s Relish Empty Glass

In 1851 an event was held that would be the largest talking point in Victorian industrial history. The event was called ‘The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations” It was intended to show all that was good about Great Britain. The Building Committee put the

Soyer’s Sultana’s sauce

design and building out to tender, 233 designs were tendered. One of those was Alexis Soyer he wanted to cooperate Marble Arch as an entryway. Also, Alexis was offered the drinks and sandwiches franchise which he turned down; Schweppes offered the committee £5,000 for the franchise which was accepted. The drinks and sandwiches were the only things sold to the public besides The Illustrated London News. Alexis persuaded his old friend George Warriner to man an exhibit stall promoting Soyer’s Osmazome Food and soups.

To Osmazome meat, make sure it has no bones or gristle or fibrous parts, place in a saucepot add liquid and boil for 20 minutes boil at 160f, then strain. Then boil the liquid until the consistency is like thick treacle. Remove the scum from the top then allow it to cool. When cold it will be a solid block, which can be used by reviving with hot gravy. The Osmazome block will last you several years. Detailed receipt in Soyer’s Modern Housewife.

During my research, I was very surprised to find a petition for a patent for his Soyer’s Osmazome Food. This would be the first time Alexis was protecting one of his inventions. It would appear he had listened to someone’s advice. But I was quickly disappointed although he had submitted a petition he had not followed through so the petition was rejected.

Soyer’s Ideas & Inventions.

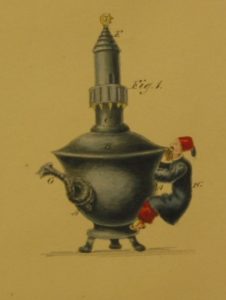

Alexis’ first design for his Crimea tea-pot

In reading Soyer’s Culinary Campaign it is noted several times by Alexis Soyer that he kept a tablet of all events. Also, if a luminary was having a conversation with him, his secretary would record all the details and then Alexis would ask said luminary to sign the document. Also, for every letter written to newspapers, Alexis would have a copy of them, even the unpublished one. When he built the Universal Symposium during the designing and changing the usage of Gore House and during the running of the Symposium. An interesting titbit I am sure Alexis would have recorded in his tablet. The night before opening the Symposium 31st April 1851 he gave a thank you banquet to some of the more popular newspapers who he had used to promote the Symposium. One of their numbers was Karl Marx who claimed to represent Neue Rheinische Zeitung. The only problem with that is that his paper had printed the last edition on 19th May 1849. [ I found this in a note by Fredrick Engels] It appears that Marx’s was just there for the food. However, all these tablets, notes and copies of

Soyer’s Scutari Teapot. see first design patent number 3712 4th May 1855

letters had been lost or destroyed.

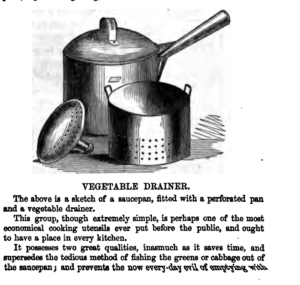

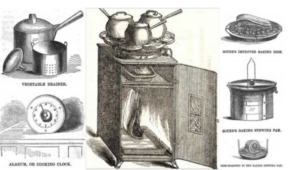

I have written about his Magic Stove under stories: Soyer’s Magic Stove or his Lilliputian Apparatus. I have also mentioned and shown his soup kitchen design as another story. On the main page under Crimea, I have introduced you to his Soyer’ Field Stoves and under The Reform, I have uploaded his kitchen designs and kitchen apparatus. Above in Blue is his design registration for his Soyer’s teapot and as you can see by the second image, he had changed the design. He tells us that it holds eight quarts and by putting the ration of tea for 20 men in the filter, then piping hot water he could serve 26 soldiers with hot tea without any sediment.

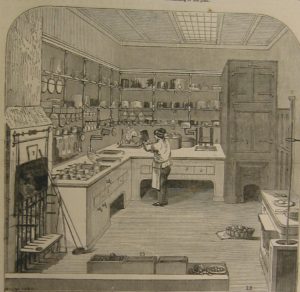

Soyer’s Miniature Kitchen which he designed for the Steam Vessel Guadalquivir.

In September 1847, Alexis was approached by a Mr Charles Harbottle he had just had a steam vessel built called Gaulalquivar no expense had been spared in its build it was 220’X24’ and was considered a masterpiece in metal. The cabins were luxurious. In style it was like an American river steamer she had a 27-foot paddle and was designed to carry passengers between islands in the Caribbean, in fact, it was the first British steam vessel seen in the Caribbean. Harbottle asked Alexis to design a luxury kitchen for the vessel, (see image) which he did, and it was built by Messer’s Bramah of Piccadilly. He invented a swinging grate to cope with stormy seas. Unfortunately, the Gaulalquivar sunk in the Caribbean two years later.

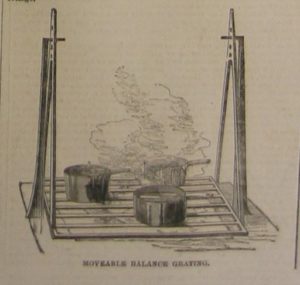

Movable balance grate

Some of the other inventions by Alexis. The last project he was involved with before his death was designing the kitchens at Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, London, using the soldier’s rations cooked a superb meal for the Battalion of Guards according to The Times 29th July 1858.

Alarum Alexis invented this for timing cooking times.

Soyer’s vegetable drainer

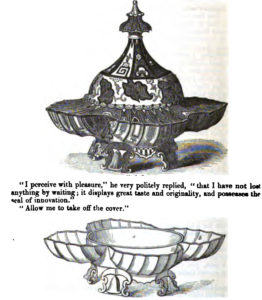

Pagodatique cullinaires

Other Inventions by Alexis Soyer

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.