20 Aug Soyer’s Universal Symposium of All nations at Gore House.

Soyer’s Universal Symposium of all Nations at Gore House.

Soyer’s Universal Symposium of all Nations, formerly Gore House.

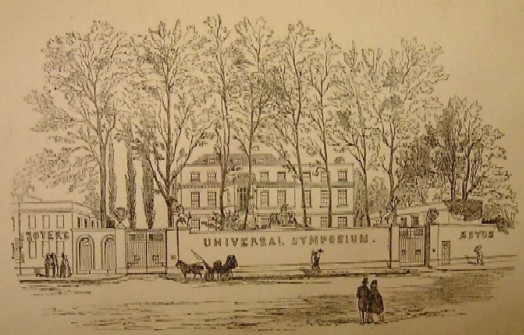

Gore House Kensington home of the Universal Symposium. The Albert Hall stands there now

In the latter part 1850, several newspapers carried an article informing their readers that the late chef of the Reform Club, Alexis Soyer, has taken a lease for six months at £600, for Gore House. Which he signed on 30th December 1850. The period covered the same time that The Great Exhibition of all Nations would be open in Hyde-Park. Gore House was opposite (Now Albert Hall) the main entranceway to the park, hence, would be opposite to the main entrance to the Great Exhibition. The house has some delightful pedigree, it was once the home of William Wilberforce who was the leader of the movement to abolish slavery. Of late it had been the home of one of the leading London hostesses, Lady Blessington who with her husband Count D’Orsay had fled the country to avoid their debts. The newspapers were trying to guess what Alexis was up to, they thought he was going to open a hotel, for several years Soyer had the idea that he wanted to open a restaurant in London, that in modern parlance would blow the minds of all that visited it. I have written much about what Alexis carried out in the 1850s. On Sunday 30th March 1851 census we find Alexis Soyer, Joseph Feeny and George Augustus Sala staying at Gore House. Sala was to become a very famous writer, but at this time he was acting as agent and manager of Soyer’s Symposium. He would later write, the vary rare book ‘Soyer at Gore House’, allowing Alexis to be named as the author. It is Sala and this book that was the main source of what we know about the Universal Symposium.

Feeny was quite a character. I don’t know how Soyer and Feeny met as he came and carried out business in Liverpool, I could hazard a guess that he met him when he was promoting his magic stove as he did go to Liverpool to do so. However, ‘Memoirs’ does tell us that there was a restaurateur who kept badgering Alexis to open a restaurant together and he would provide the finance. When Charles Dickens wrote of debts, he wrote of debtors’ prison this would normally apply to people who have been made insolvent and have no property or money. Being made bankrupt allowed you to work your debts off and then receive a Certificate of Satisfaction. It did depend on what sort of tradesman you were, and it all changed after 1861. I write this because of Joseph Feeny Liverpool merchant. Feeny had expertise in running large numbered of diners’ establishments he owned one in Liverpool called Feeny Merchants’ Dining Rooms which sat 2,500 people. On 14th November 1848, he was made bankrupt. He then went into partnership with Alexis Soyer with Soyer’s Universal Symposium. But because of an argument over François Volant, (see later about Volant) the partnership was dissolved by mutual consent on 4th July 1851, with Alexis taking on responsibility for all debts to that date [not a clever move]. We then hear of Feeny again in 1852, whereby he dissolved a partnership with Francis Edward Morrish on 2nd December 1852. However, Morrish himself was made bankrupt 23rd June 1848. Francis Feeny then opened another large restaurant in Liverpool called either Oriental Divan or Bit Hand Room. He was again made bankrupt on 2nd December 1854. He then goes on to open Feeny’s Café & Restaurant 31st July 1855, but shortly afterwards on 3rd August 1855 he died, and all his property was sold off.

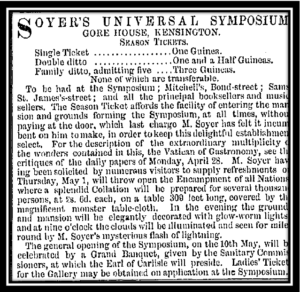

Advert for Soyer’s Universal Symposium appeared in all National Newspapers

Because of the excellent banquet, Alexis had provided at York for the Lord Mayor, Alexis received a letter dated January 1851 from the Executive Committee of the Great Exhibition offering him the food and drink concession. All his friends counselled him to submit a tender, feeling it would be of great financial benefit to him. They were very surprised that Alexis turned it down. Later, Messer’s J Schweppes & Co paid £5,500 for the tender to provide ‘temperance drinks’ only. The reason Alexis refused the invitation to tender, was that in December as mentioned above, he had committed himself to the Universal Symposium.

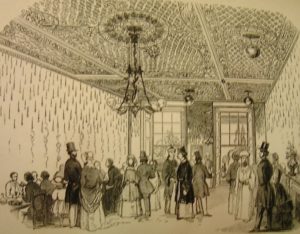

But, back to the Symposium. Its 10 am Wednesday 16th April 1851. You are at Gore House for a tour, you have paid your 2/6d and have decided to join the tour that George Augusta Sala is showing, although you see such luminaries as Charles Dickens and William Thackeray in Feeny’s group. You know this is the last day you can visit Gore House before it opens; as Soyer & Feeny have decided to end visitors’ tours as it had been slowing work down. You have heard that they have done this at Paxton’s Crystal Palace as well. The first thing you notice is the hordes of various tradespeople getting on with their work. [You might notice brackets such as these interrupting Sala’s narrative because he has missed telling you something about Gore House] “We have sent forth advertisements to the daily papers, and legions of mothers, grandmothers and aunts brought myriads of newly-washed boys; some chubby and curly-hair, some lanky and straight locked, from whom we selected the comelier youths and put them into picturesque garbs. Then we held a competitive examination of pretty girls; and from those who obtained the largest number of marks ( of respect and admiration) we chose a bevvy of Hebes, [Victorian language for a member of the Jewish race] whose rosy lips, black eyes and blue eyes, fair hair and dark hair, very nearly make me crazy in the spring days of 1851. And by the end of April, we will completely metamorphose Gore House. I am sure that poor lady Blessington would not know her coquettish villa again had she visited it; I am afraid she would not have been much gratified to see that which the upholsterers, the whitewashers, the hangers of calico, and your humble servant had wrought. As for the venerable Mr Wilberforce who I believe occupied Gore House some years before Lady Blessington’s tenancy, he would have held his hands in pious horror to see the changes we had made. A madcap masquerade of bizarre taste and queer fancies had turned Gore House completely inside out. In truth, we played the dickens with it. The gardens were certainty magnificent; there was a sloping terrace of flowers in the form of a gigantic shell and literally crammed with the choicest roses, which were seldom been rivalled in ornamental gardening. But the house itself, as you can see on entering the house, coming into the Le Vestibule, you have on the wall’s frescos of Fille de L’Orage. Hanging from the centre of the ceiling is a gigantic hand clutching the arrows of Jove, which was called the Cupola of Jupiter Tendons. The library had been kindly dealt by, [From there you walked into L’Atelier de Michel Angelo, or the Hall of Architectural Wonders, this what the library was named] save from the ceiling were suspended a crowd of quicksilvered glass globes which bobbed about like the pendant ostrich eggs in an eastern mosque. Next, we call this room the ‘Florians’ with walls and ceilings fluted with blue and white calico and struck all over with spangles. There was the Dorian room also in Calico, pink and white, and approached by a port called the ‘Door of the Dungeon of Mystery’ which is studded with huge nails and garnished with fetters in the well-known Newgate fashion. Looking towards the garden is the Alhambra Terrace and the Venetian Bridge. The back-drawing room is the Night of Stars or the Reverie d’ Etoile polaire; the night being represented by a cerulean ceiling painted over with fleecy clouds and firmament by hangings of blue gauze spangled with stars cut out of silver foil paper [Alexis had named it [Le Salle de Noces de Danaé or the Shower of Gems.] Then there is the vestibule of Jupiter Tonas the walls covered with a salmagundi of the architecture of all nations from the Acropolis to the Pyramids of Egypt, from Temple Bar to the Tower of Babel. [this was named L’Atelier de Michel Angelo, or the Hall of Architectural Wonders.] The dining room became the hall of Jewels, or the salon des Larmes de Danae, and the ‘Shower of Gems’ with grand arabesque perforated ceiling, gaudy in gilding and distemper colours. Upstairs there is a room fitted up as a Chinese Pagoda, another as an Italian Cottage overlooking a vineyard and the Lake of Como; another room is the cavern of ice in the arctic regions, with sham columns imitating icebergs, and a stuffed white fox – we brought cheap at a sale – in the chimney. The grand staircase belonged to me, [Sala called his work demisemitragiccomigrotesquepanofunniofsymposrama] and I painted the walls with a grotesque nightmare of portraits of people who I had never set eyes on saving in the print shops, till I saw the originals grinning or scowling, or planted in blank amazement before the pictorial labels on the walls. In the garden, Sir Charles Fox (built the Crystal Palace) built for us a huge barrack or wood, glass and iron which we have called the ‘Baronial Hall’ and which we filled with pictures by M. Soyer’s late wife Emma Soyer and lithographs and flags and calico in our own peculiar fashion. We hired a large grazing meadow at the back of the garden from a worthy Kensington cow keeper and having fitted another barrack at one end of it called it the Pre D’Orsay. We memorialised the Middlesex magistrates and after a great deal of trouble, we obtained a license enabling us to sell wines and spirits and to have music and dancing if we so choose. We sprinkled tents and alcoves all over the gardens and built a gipsy’s cavern and a stalactite pagoda with double windows, in which gold and silverfish floated. And finally, having engaged an army of pages, cooks, scullery maids. Waiters, barmaids and clerks of the kitchen, we hope to open this monstrous place on the 1oth of May 1851 and bade all the world come and dine at Soyer’s Symposium. [Author’s apology to the article in The Manchester Times dated 1st March 1862, titled Preparations at Gore House by Alexis Soyer.]

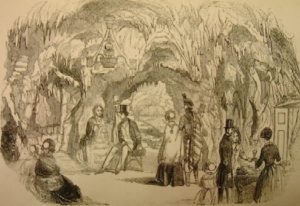

Bower of Ariadne, or the Vintage Palazzo

After touring Gore House, sit down with a Soyer’s Nectar drink and read a friendly newspaper to see if their article is similar to your visit.

“That in this world all things are mutable, perhaps was never better illustrated than in the history of Gore House, which no doubt, our reader are aware stands in Kensington Road about two or three hundred yards beyond the opposite side of the way. Time was when this noble building was the residence of philanthropic Wilberforce – at another time we find it the abiding place of the immortal Rodney – and again of the accomplished and beautiful Lady Blessington – and the rendezvous of a large portion of England literary and artistic talent. Again a change has come over the fortunes of the house and we find it tenanted by a gentleman who fills no less a place in the eyes of the world – through his talent is certainly a very different description to that of any former occupiers, albeit is one which will ever make popular among Englishmen. Alexis Soyer has already done good service to the cause of gastronomy and is now about to open the Symposium to prove to Englishmen and the numerous visitors who are to throng these shores that he can successfully carry out in practice all he has theorised upon in works 0n l’ art culinaire at prices which will render a visit to his establishment accessible to all who patronise the Exhibition over way. Soyer does not open a hotel, but he at the same time presents to the million a grand show, the house and grounds being in the style of elegance that is at once novel, extraordinary and pleasing.”

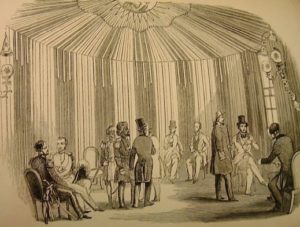

la Chambre ardente ď Apollon, or the Temple of Phoebus.

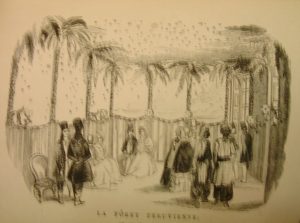

Upon entering the house, the visitor is received into ‘le vestibule de la fille de l’orage, or the cupola of Jupiter Tonans. Here is an immense hand, appertaining we are led to supposed to Jupiter, holding within hand the forked lightning, which he appears to be liberally throwing out to affright the denizens of the world, when la fille de l’ Orage, which is a descriptive catalogue we are informed is the choreographic creation by M. Soyer rises in the distance to ride the whirlwind and direct the storm, which by her emblematic of the National Exhibition shows its refulgence in the skies. Passing from this vestibule we enter l’ Atelier de Michel-Ange or the hall of Architectural Wonders, where we find views of all the most noted architectural wonders of the world such as St Pauls, The monument, the new Houses of Parliament, the tubular Bridge on the Holyhead Railway etc all mixed together in the most admired confusion as we are truly told, geography, time and place, and locality, being together set defiance. Passing onwards, we next come to la salle du Parnasse, or, Blessington Temple of Muses – a spacious gallery divided into sections by Ionic pilasters in white and gold, having panelled recesses, filled with fluted white and green drapery. In this gallery, also, there is a magnificent display of plate glass, marble consoles, golden pedestals, classic pots of fleurs of richly carved oak, apparently enriched with Transatlantic Ante-Chamber, decorated with the well-known stripes and stars of the Republic, we pass into la Cabinet de toilette a la Pompadour, or Alcove of White Roses, which is tastefully decorated with pink and white, while the mirror is encircled by a triumphal arch of white roses. This brings us into la salle des Noces de Danaë, or the British of gems, a magnificent quadrangular apartment, opening by two lofty windows, opening on a veranda and Venetian bridge. The ceiling of this room is gorgeously tinted and perforated arabesque, the prevailing colours being pale green and gold – while half pendant from this plafond are eight globes of glass, silvered on Mellish’s principle – many specimens of which, by the bye, we may mention, are scattered throughout the house, casting reflections upon all beneath, and which, when the sun is on the room, or the gas is lighted, have a most extraordinary effect. The walls of this apartment are decorated with tears of embossed gold, silver, etc looking like the showers descending from a rocket of many hues. There is but one other room, La Fôret Peruvienne, or the Night of Stars, the nature of which is sufficiently depicted by its name, to view before we come to the Grand Macedoine or staircase, painted by Mr Sala, showing the heterogeneous mixture that is likely to take place at the Great Exhibition thus we have cheek by jowl. Wellington and Napoléon, Brougham and Guizot, Russell and Disraeli, Abd el Kader and Theirs, Stanley and Cobden, Louis Napoleon and the Wizard of the North, The Great Sea Serpent and the Chartist Reynolds – and very many others, as our old friend George Robins, used to say, too numerous to mention, and which must be seen to be appreciated. Having ascended the staircase, we are introduced into l’ aĉenue des amours, or Gallic Pavilion, dedicated to the natives of la Belle France-la Chambre ardente ď Apollon, or the Temple of Phoebus, warm and glowing as crimson can make it – la Grotte des Neigres eternells, or Rocaille des Lueurs Boreeales, a representation of a northern cavern filled with pendent icicles, which makes one shiver to look at them; the Bower of Ariadne, or the Vintage Palazzo, a saloon elegantly decorated with well-executed views of Italian scenery, surrounded by vines which appear ready to break beneath the weight of the luscious bunches of grapes with which they are burdened; the Door of the Dungeon of Mystery, which loaded with chains, seems enough to appal the visitor and keep him from entering within its fitted-up chambre ˋa coucher, attached to which is l’ Œil de bœuf, or Flora’s retreat – an exquisite chambrette redolent of roses and lilies-and lapagole du cheval de bronze, or the Celestial Hall of Golden Lilies, a complete Chinese exhibition of Golden Lilies of itself. Having visited all that is worth seeing in the house, the visitor is next conducted to the extensive grounds, which are laid out with great taste à la Watteau, these grounds – which are stated to contain eight acres, and have been christened by M. Soyer Le pre d’ Orsay-are entered from the French windows of the grand saloon, first passing over a platform called the banqueting bridge à la Rialto, or the Doge’s Terrace, which gives a very fair idea of Venetian splendour. Descending from the banqueting bridge by a spacious flight of steps, we, come to the Washington refreshment room, in which brother Jonathon will be able to luxuriate in sherry cobblers, egg nogs, goinners, flashes of lightning, gin slings, brandy Pawnees, hailstorms and the thousand and one other transatlantic drinks of which we have heard so much, and hitherto known so little. Then we have Le Pavillon des Zingari, or the Gipsey-Dell -the impenetrable grotto of Ondine, or Hebe’s mistake, in which those who are venturous enough to attempt to enter may calculate upon receiving a gratuitous shower bath -the Baronial Hall, 100 feet long, 50 feet broad, and 30 feet high erected by Fox & Henderson, which is to be decorated by the paintings of the late Madame Soyer, and the works of Count d’Orsay – la pavilion Monstre d’ Amphytrion, or Encampment of all Nations, capable of dining 1500 persons at one and the same time, of the celebrated monster table-cloth, 130 yards long, which takes two men to lift – and numerous statues standing on grassy pyramids, fountains and other decorations”. [Author’s note: The Encampment of all Nations was the largest public eating arena in London.]

La Grotte des Neigres Eternells, A Cavern of Ice

“Then again, the lovers of gastronomy will be enabled to regale themselves in anticipation of the good cheer which M. Soyer will be happy to supply them, by watching daily the roasting of a whole ox in front of the monster pavilion – or the cooking by gas of 200 joints at the same time in the new kitchen erecting for the purpose. The house and grounds are to be thrown open to the public for view this day for a ‘consideration’, though they are not at present in such a state of completion as to enable the proprietor to commence business. On the 10th May, however, the hotel doors will be thrown open and the Baronial Hall inaugurated by a dinner of the Sanitary Association, at which the Earl of Carlisle will preside. We are further informed that M. Soyer has already been engaged by leading members of the nobility to provide upwards of twenty entertainments for themselves and friends in his gastronomic palace.” The Morning Post, April 28th, 1851.

Although Newspaper articles and advertisements in all papers and word of mouth give us different dates that the Symposium opened, from the 3rd, 10th May 1851. It did not open to the public until 17th May 1851. They were behind in their schedule and lost 16 days of 278,009 people going to see the great attraction 200 yards from their door, but not being able to buy any acholic drink. The Great Exhibition was a temperance establishment. Scattered outside around the Baronial Hall and the Encampment of all Nations were roasting pits filled with coal fire and gas stoves with 600 jets of gas and every day a whole ox was cooked. The main kitchens were in the basement of Gore House. Walking around the grounds each night were jugglers, clowns, troubadours and singers and every night there would be a firework show. Helping to keep everything running smoothly and diners served swiftly, were 100 Symposium pages, and of course, Alexis had designed their outfits. Alexis kept the frontage of Gore House very simple only adding the name ‘Soyer’s Universal Symposium’. He also had a monster gas meter in the front garden, so people could see the gas consumed by the Symposium. In the trees, he had a gas-illuminated light with the name Soyer on it.

Le Salle de Noces de Danaé or the Shower of Gems.

One of Alexis’s traits was his complete adulation of the nobility and the rich. He also took people at face value, sometimes to the point of gullibility. It took him a long time to see the bad in people and he often suffered because of this. With Gore House, Alexis’s original intention was to run the successful Symposium there until October, then to use the profits to fund his Cookery College. However, the Symposium was far from successful. Because it was well frequented by the rich, the nobility and by fashionable people of the day, whom he entertained at the Baronial Hall, Alexis thought that it was a success. However, it was not as popular with the hoi polloi and professional classes that were catered for at the Encampment of all Nations. At first, when the Symposium opened in May, many complimentary letters were received. However, by June these had turned into complaints about the food and management. The letters complained of slow service, the bad manners of some of the pages, cold food and food with no taste. The last was the worst for Alexis as ordinary people were complaining that the food did not match the reputation, they had of the Great Soyer. In the middle of June, Alexis had a crisis meeting with Joseph Feeny his partner, George Warriner who was overseeing the food served at The Encampment of all Nations and Francois Volant. Feeny was very unhappy; he felt he was not getting the return on his investment as expected. Warriner complained about the staff as he had no overall control of them because Alexis had sub-contracted them all in, from Simmonds & Co. Joseph Feeny wanted to dissolve the partnership as he had no faith in Volant and his plan as outlined in ‘Memoirs’ as ‘Report on the Symposium’. Soyer had asked Volant to become the General Manager and implicate his report [Author’s note. I was rather surprised that Alexis picked Volant when the ideal man was sitting beside him – George Warriner.] The partnership between Feeny and Soyer was dissolved instantly on 4th July 1851. Soyer without a partner was in a desperate situation, so he approached his old partner, Alexandra Symons from ‘A. Soyer & Co.’ to come on board which he did. Symons quickly demoted Volant and got rid of his plan. Alexis was desperate for ideas to boost trade, talking to his very old friend Louis Jullien, who in turn suggested a music hall, near the Encampment of all Nations, enhancing diners that had eaten at both halls that they could ‘wine & dance’ the night away. Alexis must have forgotten in his lease he had agreed that there would be ‘no balls, concerts or fetes’, taking place at the Symposium. Alexis had great problems applying for a music license in the first place and knew he would need another license to cover the potential music hall. This is when he came across the stubborn chair of the Middlesex magistrates – Thomas Pownall. What Soyer did not know about Pownall that he was a leading light of the local temperance movement, who, on receiving Symposium’s application for the extra license decided to carry out a surprise visit. Unfortunately, the night Pownall picked to make his surprise visit, there were several rumbustious and inebriated diners. The magistrates refused the license after hearing Pownall’s report. One, Cornelius Butler spoke to the same effect claiming the Symposium was a great public nuisance. So, no license.

La Foret Peruvienne; or, The Night of Stars.

Alexis sensing the tide was against him, suddenly decided to close the Symposium, which he did without any notification to his partner, staff and visitors. He left a note on the door claiming he would pay all the debts and wages that were owed by the Symposium. [Author’s note: I think the reason why he closed was that he had run out of money and could not afford to let it open any longer.] While it was open the Symposium took £21,000, but it had cost £28,000 for the same period.

No sooner had he closed the Symposium he was facing various court cases. John Simmonds was the first to act and sued Soyer & Symonds and was heard 19th October 1851. Simmonds was suing for the sum of £686, claiming after Feeny left he had made a new verbal agreement with Alexandra Symons. Symons denied this. The Lord Chief Justice Jarvis claimed the law does not recognize ‘verbal agreements’ and Simmonds lost his case.

There were several other cases but the one that hit Soyer the hardiest was Francois Volant, on 2nd December 1852 in front of Lord Chief Justice Jarvis he sued Soyer and Symonds for lost wages of £54,18p. Alexis defaulted, (pleaded guilty). But, Symonds wanted to defend the case. he claimed he had a receipt signed by the plaintiff that he had been paid up to date. Volant disagreed and claimed that part of the wording on the receipt was added after he signed it, the judge and jury agreed and found for Volant. Chief Lord Justice Jarvis, said that perjury or forgery had occurred and confiscated the receipt, in case the plaintiff and his team want to bring a case of forgery against Soyer and Simmonds. Much to everyone’s surprise, Volant did just that, his case was heard on 1st January. However, the judge throws the case out saying it was not worth considering. The Judge was again Lord Chief Justice Jarvis, who was a Reform Club Member.

On 1st May 1853, Soyer’s partnerships with R. Gibbs, R Baker and J. E Piper, Nectar Makers, was dissolved. On 17th June 1853, Soyer’s and Symon’s partnership was dissolved. In 1854 in The Times newspaper, Volant apologised to Alexis Soyer, claiming his argument was against Symons, not Soyer, Alexis did not accept the apology and did not mention Volant’s name again. He would have been highly annoyed to have found out that Volant came to his funeral – sacré bleu

Business card of Alexis Soyer.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.