Alexis’ Relationship with Francesca Cerrito.

Francesca (Fanny) Cerrito. Fanny, as she was more popularly known, started her affair with Alexis in...

More about The Author:

Frank Clement-Lorford devoted three years to intensive research into the life and career of Alexis Soyer, both here and in France. His interest was initially generated by his ex-wife, whose grandfather, Nicolas Soyer, was widely believed to be the grandson of Alexis. Nicolas was a famous chef in his own right, achieving notoriety in the early years of the 20th century with his novel system of ‘Paper-bag Cookery’, which became a culinary phenomenon across Europe and America. However, because of recent research, everything about Nicolas Soyer must be rewritten, Frank has discovered that his real name was Marius Soulier, not Nicolas Soyer which he called himself for several years, neither was he the grandson of Alexis Soyer. Frank quickly realised that all existing work on Alexis Soyer was riddled with inaccuracies. The first full biography of Soyer, written in the 1930s, had been based exclusively on a contemporary memoir written by a disgraced secretary, which was full of errors. Future biographers, on discovering that few primary sources had survived Soyer’s death, simply went on to compound the mistakes found in the early biography. Therefore Frank – an experienced genealogist, who also, has an MA in Historical Research – was able to begin from nothing and using a vast range of library and archival sources, painstakingly pieced together the true picture, the first true picture of this extraordinary man. The result, Alexis Soyer: The First Celebrity Chef, is a fascinating work, pulling together a wealth of facts and illustrations that have never been seen before.

and using a vast range of library and archival sources, painstakingly pieced together the true picture, the first true picture of this extraordinary man. The result, Alexis Soyer: The First Celebrity Chef, is a fascinating work, pulling together a wealth of facts and illustrations that have never been seen before.

Frank Clement-Lorford is a retired businessman living in Guildford, Surrey. Alexis Soyer: The First Celebrity Chef – is his first book. Written by Alexandra Garlick in 2001.

Please contact me at. frank.clementlorford@gmail.com

When I first started my research in the late 1990s there was very little known about Alexis Soyer. In the world at large Alexis’ name in history was largely forgotten. Over several years of intense research in England and France and with the help of the internet I discovered more about Alexis Soyer. My aim was to get Alexis’ name recognized in history. Previous authors had not been fair to Alexis and much of what they had written was erroneous. I opined that any author that wanted to write about Alexis I would help by adding my research. I helped Ruth Brandon with her book ‘The People’s Chef’ and I also helped Ruth Cowen with her book ‘Relish, The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer. Both Ruth Brandon and Ruth Cowen read my Book ‘Alexis Soyer, The First Celebrity Chef, before writing and publishing their books. Therefore, they did not repeat the mistakes of Langley, Ray and Morris. Which I am very grateful for.

Historically, before 1999 there had been four biographies written about Alexis Soyer, Namely. ‘Portrait of a Chef. The Life of Alexis Soyer’ by Helen Morris, ‘Alexis Soyer. Cook Extraordinary, by Elizabeth Ray and then ‘The Selected Soyer’ which was compiled by Andrew Langley. Any newspaper or magazine article was based on information in these three books. Unfortunately, many webpages on the internet are also based on these three books.

In 1859 a book was published named ‘Memoirs of Alexis Soyer’ Compiled and edited by F. Volant & J.R Warren, his late secretaries. They were assisted by one J.G Lomax, an esteemed friend. This book did such damage to Alexis Soyer’s reputation because it contained so many errors. Sadly Morris, Ray and Langley all included most of these errors in their books, they really cannot be blamed as they must have thought that all three writers of ‘Memoirs of Alexis Soyer’ were trusted, friends. Because of this, I will be adding a post to my website, below stories, called ‘Memoirs of Alexis Soyer’ where I will attempt to put right these many errors that the book contained.

When Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Secretary for War (1861) said, ” The indiscretions of biographers adds a new terror to death’. This was certainly true for Alexis Benoist Soyer. I have never believed that biographies of a person should be written sycophantically it should be a ‘warts and all’ book and the story should not contain fictional events. Therefore, I was forced to write my book, this website and my previous one www.soyer@co.uk in a chronological sequence as much as empirical evidence would allow. Much of Alexis’ story remains untold as I could not find supporting evidence for certain events. However, in writing, about historical characters like Alexis Soyer ‘true facts’ are very rare. I hope you enjoy this website and possibly my book and come to feel you know who Alexis Benoist Soyer was, and what he stood for.

During his time in the Crimea, The ‘Morning Chronicle’ said of Soyer “That he saved as many lives through his kitchens as Florence Nightingale did through her wards.” At that time soldiers were given their food rations directly, where they would put metal buttons, or pieces of metal in the meat, so they could recognise their food after it had been cooked, Soyer immediately put a stop to that practice.

Alexis Soyer was born in rue Cornillion, Meaux-en-Brie on 4th February 1810. The youngest son of Emery Roch Alexis Soyer and Marie Madeleine Francoise Chamberlan, late grocers of rue du Tan, Meaux-en-Brie. However, when Alexis was born the family had fallen on hard times and his father took on several jobs, even working on the new canal as a labourer, Two elder brothers Paul and Rene died in their infancy, leaving two other brothers, Philippe and Louis. His Father died when Alexis was eight years old and his mother remarried and moved to Crecy France, at the age of nine he joined his brother Philippe in Paris, Philippe was already an established chef. By the age of seventeen, Alexis was a celebrated chef with 12 junior chefs working under him. Alexis had previously trained at Rignon (Georg Rignon) but now worked at Douix, Boulevard des Italiens, Paris. Again, for various reasons, in 1831, Alexis left France, and came to England to join his brother, Philippe Soyer who was now chef for Adolphus Guelph, Duke of Cambridge.

In five short years Alexis quickly established himself with the landed gentry and nobility and become a chef de cuisine of note. In 1837 he was offered the job at the newly formed Reform Club – where he helped design the kitchens with Charles Barry. Also in 1837, Alexis married the celebrated artist Elizabeth Emma Jones. Emma as she preferred to be called, was prolific in her work-rate. She first exhibited at the Royal Academy at the age of ten – she also had some very strange ideas about social class and etiquette. Such as “In walking keep your feet extended out nearly to a right angle with your body, and seldom let more than the points of toes touch the ground; keep your shoulders at the same time well extended back; and, in a word, during the whole of your gait, suppose yourself to be anything but what you are.” or “To speak naturally, to act naturally, are vulgar and commonplace.” Emma was rather a delicate soul and she died in 1842. She simply died of fright on a day of heavy thunderstorms. She was with child and her death has also been described as ‘dying in child-bed.’

Alexis other great love was Fanny Cerito; Fanny was one of the leading ballerinas of the day. Her father disapproved of the relationship, she married Arthur St Leon. The marriage failed. She and Alexis had a secret relationship until his death.

Whilst at the Reform Club, Alexis hearing about the plight of the Irish peasants, during the potato famine of 1847, asked by Russell’s government for help. The Reform Club granted him leave of absence. Alexis went to Dublin, Ireland, and set up the first properly designed soup kitchen, where he served his famine soup, which he had formulated for his soup kitchen. At the peak of the soup kitchen it served five thousand people daily. It is claimed that Alexis’s efforts were fundamental in saving several hundred’s of lives. Also Alexis opened an art gallery showing pictures painted by his late wife Emma Soyer, it was called ‘Soyer’s Philanthropic Gallery.’ He used monies he made from this to fund several soup kitchens for the poor – in various districts of London.

Alexis was concerned about ‘Consumption’ as he had lost several family members to it. Also he had lost both his brothers before they had reached the age of 50, Philippe from consumption in 1840; therefore in 1850 he tended his resignation to the Reform Club – using the pretext that the Reform were to allow members of the public into the coffee-room; which he disagreed with. Alexis had threaten to resign several times in his career at the Reform, most notably in 1848, but this time it was accepted by Lord Marcus Hill. Who remained a lifelong friend of Alexis.

In the latter part of 1850, in partnership with Joseph Feeney later Alexandra Symonds, Alexis leased Gore House (stood where the present Royal Albert Hall now stands,) and in 1851 opened ‘Soyer’s Universal Symposium to all Nations’ He tried to catch the excitement of the 51′ exhibition. But because it was Soyer – it was doomed to fail. It was the most flamboyant fashionable restaurant ever seen in London. Each room was decked to some extravaganza theme such as ‘The Grotte Des Neiges Eternelles’ and ‘La Chambre Ardante D’Apollo.’ In the grounds he had a large marquee called ‘Baronial Banqueting Hall.’ He hoped to entertain and feed 5,000 people daily, with different priced menus for different classes of people, after three months he closed it down with a loss of £7,000. Approximately £440.000 in today’s -2001 -money.

From 1851 to 1855, he toured the country promoting his cookbooks and the ‘Magic Stove.’ Also masterminding sumptuous banquets and feasts – always maintaining that any food leftover be given to the poor, In 1855, Alexis became very concerned with the plight of soldiers in the Crimea. In daily reports in the ‘London Times’, it was describing horrendous conditions in the hospitals at Scutari and Balaclava, poor rations, and how men were dying of food poison, malnutrition and cholera – let alone damages inflicted by the enemy. He volunteered at his own vocation and expense to go to The Crimea, to see if he could help matters. He gained through the offices of The Duchess of Sutherland, Lord Panmure’s authority, to correct any matter he saw fit. Prior to his leaving he invented the ‘Soyer’s Field Stove’ (which the British Army was still using 120 years later.) He worked in close liaison with Florence Nightingale to correct the dietary and food regimes in the hospitals.

Soyer organised that each regiment had a trained chef who’d collect all the rations and prepare food for the men (this gave birth to the Army Catering Corp., many years later,) using his Soyer’s Field Stove, which could cook food in any weather conditions. He devised new diets for these regiments.

On his return from the Crimea, Alexis was not a well man. He wrote his final book “Culinary campaign’ and saw that published. Alexis died in 1858 and was laid to rest with his wife under the memorial ‘Faith’ in Kensal Green Cemetery.

During his time Alexis was a prolific inventor and author, he wrote eight books and his ‘Instructions for Military Hospital Cooks’ was published in 1860. With the various titles of his cookbooks he reached all levels of society. On his death a creditor called David Hart, a wine merchant, whose father started the brand name Lemon Hart Rum, seized all of Alexis’s goods. A year after Alexis death, Hart sold 50 of Emma Soyer’s paintings at Christie’s auction house [8th March 1859]. All his paperwork and notes of his life have been lost. Therefore because of David Hart very little is left of Alexis Bénoist Soyer. He received no rewards from his adoptive country for all his humanitarian deeds – he’s simply the man history forgot. Yet during his time he was considered the Greatest chef in the world.

It is somewhat of regret that America recognised the genius that was Alexis Bénoist Soyer – more so than his adopted country. Several books have been written about Alexis Soyer, but three authors stand out as not doing any research and simply plagiarising other books – the first being Helen Morris’s Portrait of a Chef, (1938). The second being Andrew Langley’s The Selected Soyer (1987). The third being Elizabeth Ray’s Alexis Soyer Cook Extraordinary. (1991) All these authors took the basis of their books from ‘Memoirs of Alexis Soyer,’ written by Volant and Warren, who published their book the same month as Alexis’s death in August 1858. Unfortunately for these authors there were some glaring mistakes in ‘Memoirs,’ which some basic research would have found.

By the time Mr Langley wrote his book – it was generally accepted by all, that Alexis Soyer did not write ‘Pantropheon’, but he allowed this book to be published with his name as author. In fact the author of’ Pantropheon’ was M. Adolphe Duhart-Fauvet, with the last chapter ‘Modern Banquet’ written by Soyer. Volant knew that Alexis had not written Pantropheon as he supplied many of the images for the book. I point you to this, Francois Volant and James Warren were Alexis’s secretaries One being French, the other English – Alexis always maintained either one secretary who was adept in both French and English, or one for English and one for French. Until her death his wife acted as his secretary. The only time Alexis put pen to paper was for his signature. In all other matters he dictated to his secretaries.

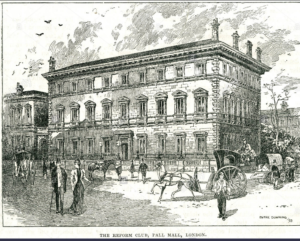

The Reform Club, Pall Mall London

The Reform Club, Pall Mall, London circa 1893. Courtesy of Guildhall Library..

All the books written about the Reform Club and Alexis Soyer such as ‘Memoirs of Alexis Soyer’ by Volant & Et Alii 1858. ‘Reform Club’ by Woodbridge 1974, ‘The People’s Chef’ By Brandon 2004 and ‘Relish’ 2006 by Cowen claim that Alexis was made head chef in 1837. However, I found in a Committee book in the Reform Club archives the following dated 2nd March 1838 that complaints had been made against the cook Williams who was discharged. Complaints made against Cartwright the present cook who was discharged with a month’s notice. Resolved that M. Soyer be engaged as cook as long as his character is ascertained, and he is given a 3-month trial. The first chef of the Reform Club was Auguste Rotivan he was appointed 3r June 1836, but only lasted three weeks. Therefore, it looks like the Reform Club had two further head-cooks before Alexis Soyer.

What Alexis was not to realise, that when he left the employ of the Duke of Cambridge, was that he was going to have trouble with the hierarchy of command. When he worked in private houses, he was head, the kitchen was his territory and you entered the kitchen as his guest – even if you owned the house. What Alexis did not realise with gentlemen’s clubs and political clubs such as the Reform was that committees ran them; Alexis had difficulties with this as will be seen later in this tale.

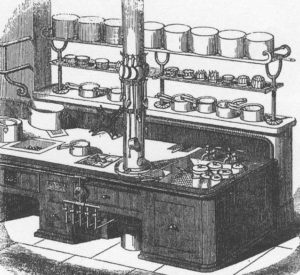

Reform Club the Kitchen published by B Mead

Prior to 1832, Conservative Members of Parliament tended to be wealthy landowners, If such a person decided to stand as a Member of Parliament, all they had to do was to persuade their friends and other major landowners to vote for them, or to buy the seat from a landowner – for which there was normally no opposition. Some ‘Radical Whigs’ of the Liberal Party decided that this was wrong and to avoid this happening in the future, it required an electoral reform. They proposed that all men who owned property over the value of £10 could vote, thereby opening Parliament to shopkeepers and the middle-classes. When this eventually passed through the House of Commons, the House of Lords rejected it. The Liberal Party (As ‘Cavaliers’ gave birth to the Conservative Party; the Roundheads gave birth to the Whig Party). The Whig party became the Liberal Party in the 1830s, but many members still referred to themselves as ‘Whigs’ and the Whig party. So, whereas today you have ‘The Left’ or ‘Right’ of a party, in the 1840’s you had the ‘Whigs’ of the Liberal Party. threatened to flood the House of Lords (King William IV agreed with the House of Lords, and the government of the day fell, but because of the outcry he eventually accepted and put his signature to the act.) with newly created Whig peers. The House of Lords conceded and in 1832, The Reform Law was passed.

The more radical of the Reformers felt that a new Clubhouse would be needed. The Whigs of the party met at The Westminster Club at 34 George Street, which was later renamed The Westminster Reform Club. The Westminster Reform Club closed 9th May 1838. The more radical MPs got together at the house of Edward Ellice MP and decided to create their own club, which would be called the Reform Club. They purchased 104 Pall Mall for £20,000 and adapted the houses for club use They employed Decimus Burton to design the changes needed. The doors of the Reform club opened 24th May 1836 with 998 members and a waiting list of 400 that had to be balloted. The dining room could only hold 50 diners. On the exit of M. Rotivan, which left the Reform Club without a resident chef, the members started to use the facilities of Horn’s Tavern nearby, where the landlord supplied the food for their various functions, however, the tavern could only seat three hundred guests. It quickly became apparent that 104 was going to be too small for their needs, so the Committee of the Reform Club decided to rebuild the Reform Club by demolishing the existing premises and having a new building designed and built. All the land for the Reform Club was actually owned by the Crown. They asked several architects to quote, All the architects’ designs were put up on the committee wall and the favourite one was awarded £100, this was Charles Barry, who had just finished the New Houses of Parliament. The building committee of the Reform awarded him the contract and the building contract went to Grissell & Peto, York Road, Lambeth, having just finished building St James Theatre. For the period of construction, the Reformers leased Gwydyr House- Now houses The British Government’s Welsh office – and moved into there 12th May 1838 until March 1841. In April the following advert was placed with the Chronicle, Globe and Carrier, simply saying “The Reform Club, 104 Pall Mall. The Club-house will be opened to the members on Tuesday 24th instant.” By its completion, the Reform club building had cost £84,042 plus Mr Barry’s bill of £3,393. Kitchen accoutrements accounted for £674 of that figure.

Alexis quickly established himself at the Reform Club. Members revelled in the food that their new cook was producing, delicacies beyond their imagination, entrees never heard of before. Soups that were out of this world, sauces so remarkable and too abundant to mention. Louis-Eustache Ude’s often misquoted quotation sheds light on the English and their sauces, “It’s very remarkable that in France, where there is but one religion, the sauces are infinitely varied, whilst in England, the different sects are innumerable, there is we say only one sauce.” Nobody but nobody produced desserts as Alexis presented them to the table. Alexis Soyer at the Reform quickly became the talk of London. Lady Blessington of Gore House, the leading society hostess of the day, said this of the Reform Club diners, that they “Prefer a well-dressed dinner to the best-dressed women of the world.” The Times said, “Alexis Soyer has taught people to dine, not to feed hunger.” The enfant terrible of Montmartre had conquered London; whereas up to this time Louis-Eustache Ude was considered the King of gastronomic London and Alexis his Crown Prince. Louis-Eustache Ude was dethroned and Alexis succeeded to the title. However, one thing that Alexis had to be grateful to Ude was that Ude’s starting salary at Crockford’s was £1,200. This was to set a precedent for clubs that to get a very good French chef – they would have to pay.

On the 28th June 1838, the coronation of Queen Victoria took place and the Reform Club put on a grand breakfast for the same day. Alexis served ‘déjeuner à la fourchette.’ which consisted of : —

Bouillon Aux Œufs.

Epelons en Brouchelles.

Paté á la Muretiton.

Tenates Sculées.

Salade á la Jardiniére

Jambon á la Gélée.

Ponequets au Confiture

Fruits et Dessert.

He catered for the 500 club members and 800 guests – mainly ladies. Although it would be well over a century before the Reform Club accepted women as members in their own rights, it was one of the very first to welcome them as guests of members. As Queen Victoria was the first monarch to reside at Buckingham Palace, hers was the first royal coronation procession to leave from there on its way to Westminster Abbey. To enable a certain number of their guests to see the procession the committee arranged for scaffolding to be erected under the supervision of Mr Charles Barry in the front of Gwydyr House. This allowed up to six hundred ladies – men not allowed – to view the royal procession. In the adjoining garden to Gwydyr House, a bandstand was erected and Johann Strauss -the waltz king – and his ensemble played such overtures as Pré aux Clercs, La Banquet and his Die Khrohnung Waltzer. For this, he was paid the princely sum of £30. Such gaiety and merriment were had on that day. Lords, ladies and gentlemen celebrating, dancing in the gardens, a woman on the throne – a new era had started!

Gas stoves at the Reform Club. Notice the 5 gas-pipes at the bottom of the stove.

This was the first time that Alexis had to cook for such many people. He was not only up to it, but he also excelled at it. Again, members and their guests were in full praise of the lunch they had been served. Newspapers such as The Illustrated London News and The Morning Chronicle carried reports the next day of the breakfast. Alexis now had settled into his job as the chef of the Reform Club, a job he was to make his own for the next decade, where he would go from strength to strength. In Gastronomic Regenerator he described his work over a 10-month period. He cooked 25,000 dinners for Reform Club members. He cooked at 38 dinner parties which comprised 70,000 dishes, he also had to supply meals for 60 Reform Club servants and on top of that show 15,000 people around the Reform Club Kitchen. On top of this, he started a very lucrative business deal with Messers Crosse & Blackwell for them to market the various new sauces he created. [In my eBook ‘Alexis Soyer, The First Celebrity Chef’, I describe the Reform Club kitchens in some detail. For reference I used the information in Gastronomic Regenerator and the 4th March 1844 The Builder Newspaper]

The Reform Club Banquet to Ibrahim Pacha. The Illustrated London News

During his tenure at the Reform Club received many platitudes, he came up with several inventions some still used today. I have added an image of the kitchen; the original was a metre long and used to be sold by the Reform Club. Alexis was allowed free range from Charles Barry in designing the kitchen. Alexis installed Gas cookers in the Reform Club kitchens, besides the normal fires for roasting meat. Alexis Soyer is accredited as the first person to use gas for cooking outside. He did this in Exeter in 1850. He installed the gas cookers in 1841, which was supplied by Smith & Philips, (This company did very well out of Alexis and one of the partners Charles Philips became a very good friend. He even named one of his son’s Alexis Soyer Philips, who unfortunately did not live up to the name Alexis Soyer in 1860 he was caught stealing 4 ounces of pearls from his employer and was sentenced to 3-months hard labour), who also built his Field Stoves used during the Crimean War. I am not sure if Gas Cookers where the first for Pall-Mall but using gas for street lighting was.

In 1850, Alexis Soyer left the Reform Club, his mentor Lord Marcus Hill wanted him to stay but recognized that Alexis needed to leave. During his time, he had upset committee members and ordinary members. At one time he was asked to leave but reinstated a few days later. Several members were glad to see him go as they did not like that Alexis was known as Alexis Soyer of the Reform Club. Some still considered Alexis as just a servant and that the Reform Club should have come first. During the 1850s Alexis concentrated on promoting his Magic Stove. However, in the 1851 census staying at Gore House (The previous home of Lady Blessington and Count d’Orsay, and the one time home of William Wilberforce), were Alexis Soyer, Joseph Feeney and George Augusta Sala. The reason why Alexis had to turn down all offers of employment was that he had gone into partnership with Joseph Feeney and their plan was to open a spectacular restaurant alongside, The Great Exhibition. They leased Gore House and employed Sala to help them. The restaurant was going to be called Soyer’s Universal Symposium.

Reform Club kitchen Plan, original was a metre long and was sold by The Reform Club.

Below are some of the new devices Alexis Soyer installed into the Reform Club Kitchens.

Oh, what a lovely war.

British Light Calvary Brigade Known as The Charge of the Light Brigade

In my ebook ‘Alexis Soyer, The First Celebrity Chef’ I go into great detail about the Crimea War. So this will just be a brief synopsis. It is extremely difficult just writing about Alexis’ time in the Crimea, because, there are so many adventurous and heroic stories it is easy to segue to them such as The Charge of the Light Brigade. The Crimea war was a war waiting to happen. Turkey was watching Ibrahim Pascha with his Egyptian army gain territories bordering on the Ottoman Empire, territories such as Syria and Palestine. Worried about these advances the Sultan of Turkey asked Russia for protection. Russia, for the last few years, had been trying to get a footing into Asia Minor and Turkey. Watching all this happen was France and Britain who were supporting and encouraging Pacha [See Reform Club for a picture of Pacha being dined at the Reform Club]. They persuaded Pacha to pull out of Syria and Palestine. This persuaded Turkey to relax its agreement with Russia.

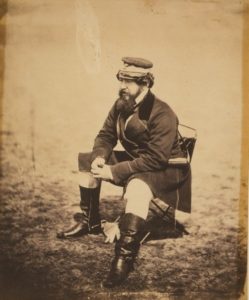

A drawing of Alexis Soyer 1855, whilst in the Crimea.

This so-called peace did not last very long. Christian countries in the Otterman Empire were constantly complaining about the Sultan’s harsh treatment. In Palestine, Catholic monks were relentlessly bickering with the Orthodox monks about the countries religious relics. France supported the Catholic monks whilst Russia supported the Orthodox monks. Riots broke out between the two factions, because of these, Russia in trying to wrestle control in the area demanded Turkey accept their guardianship again. France with the backing of Britain opposed that proposition. Russia marched on Turkey, whereby Turkey declared war on Russia on 5th October 1853. After a disastrous sea battle between Russia and Turkey where 5,000 Turks were killed, this forced Britain to declare war on Russia on 27th March 1854, France followed declaring war the next day.

Very soon the British press was inundated with stories about the Crimea. Two leading Times journalists led the way on these stories, writing about the conditions for the wounded, living conditions, the state of the kit and condition of the soldiers and how dreadful the campsites were. France had arrived in the Crimea before Britain and had commandeered all the best sites and barracks. The British public was hounding their government about the conditions. The government needed some good press stories. Along came Alexis.

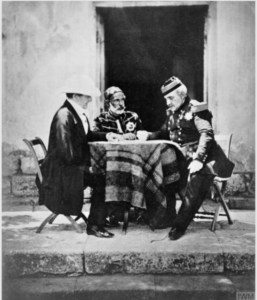

Lord Raglan, Omar Pasha and Marshal Pelissier. Alexis met all of them and they saw his cooking demonstrations.

Alexis had not ignored the articles coming out of the Crimea. He had written to The Times and other newspapers with his design for a mobile stove, which would be a horse-drawn boiler that could cook whilst the army was on the march. The patent office was inundated with designs for Crimean Stoves, even one design from Price’s Candles. Several soldiers had written to the press asking Alexis to help. But, in February, The Times Leader written by William Russell. It explained the terrible conditions for soldiers getting their rations and trying to cook them, especially after fighting all day at the front. It begged Alexis to come up with some simple receipts. (in Victorian times chefs normally referred to recipes as receipts). The British soldier was expected to pay 4½p per day for their daily ration, even if they were wounded. The ration consisted of 1lb of bread and ¾lb of meat. The army did not supply any cooking facilities, soldiers had to create their own. Alexis Soyer was horrified to learn that soldiers were combining their meat ration into one cooking pot and putting a piece of rag or a piece of metal or a brass button or badge into their meat so they could identify it. Needless to say, most of the meat was uncooked and caused food poisoning. Alexis decided ‘there and then’ to go to the Crimea, at his own expense and see what he could do. He wrote this in answer to the leader and it was published in The Times the next day 2nd February 1855. Two other people who were also affected was the Jamaican nurse Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale.

Camp Cooking Crimea before Soyer

On hearing about Alexis decision to go to the Crimea, Lord Panmure Secretary of State for War, through the good offices of the Duchess of Sutherland asked for Alexis to come and see him. He asked Alexis for further help whilst he was in the Crimea, to see if he could arrange cooking facilities for all the soldiers, to check the diets of healthy and wounded men and to check the hospitals cooking arrangement. Alexis agreed by saying “ I want complete autonomy on invalids and soldiers’ diets”. Not surprisingly Panmure readily agreed, despite making a similar promise about the invalids diet to Florence Nightingale who had left for and arrived in the Crimea 4th November 1854. By the time Soyer returned to Panmure’s office. He had designed a stove, approached Smith & Philips to make him a scale model. On showing this to Lord Panmure who agreed that the army would commission them. The model was of Alexis’ famous Soyer’s Field Stove.

William Russell, The Times Reporter

Alexis travelled to Sebastopol, stopping off at places of interest. His journey took 6 weeks, during this time people were writing to the Times and other newspapers, asking if he was on an urgent mission why was his journey taking so long? Soyer was surprised at the conditions in port. In the water, there were many dead rotting horses which smelt terrible and all the main street were covered a slimy, black liquid mud. The next day, Alexis toured all the hospitals to inspect the kitchens. At Palace Hospital he found all the officers’ meals were being prepared by an Italian cook. Whilst, the privates and non-commissioned officers were having to fend for themselves. They were cooking their meat tied up with dirty string and then skewered on a wooden chair leg. The meat was served first which was cold, then the soup was dished up secondly. He asked why they were doing that way. He showed them the meat was only cooked on the outside, he was told the men only had one plate each, this had been given to them by a charity called ‘Crimea Hardship Fund’.

Next day he exhibited in front of members of the Sanitary Commission, senior officials and officers and Florence Nightingale what could be done with some modest rations. How to cube the meat for ease of cooking, making a vegetable and barley soup, which he poured all over the meat keeping it warm until the last man was served. While he was there he noticed all the kitchen stoves were in need of re-tinning, which he had done, over the next few days, he had written receipts for the invalid and wounded soldiers, showed the orderlies how to cook in different ways and techniques.

Lady Stratford de Redcliffe (wife of the British Ambassador) suggested he should have an official opening ceremony for Barrack Hospital kitchen, forever the showman, he agreed. Therefore on 9th April 1855, Florence Nightingale and her team, hospital doctors, patients and the walking wounded, members of the Sanitary Committee, officers and their wives were in attendance, as Alexis showed all his improvements and new diets, the day was a great success. Several days after he had opened the kitchen at Barrack Hospital, Major-General Sir Robert Vivian, who oversaw the Turkish contingency, visited Scutari. He asked Soyer and Nightingale to show him all that they had achieved. After being shown around, he said, “Monsieur Soyer, Miss Nightingale’s name and your own will be forever associated in the archives of this memorable war.” In one name he was right, in the other, he was not. [however, that is improved over the last 20 years].

The Morning Chronicle writing about conditions at Scutari Hospitals wrote ‘the man at the moment is M. Alexis Soyer, he has saved as many lives through his kitchens as Florence Nightingale has through her wards’. On 22nd May Alexis and Florence Nightingale left Scutari and sailed to the Crimea. The day after their arrival they toured all the hospitals. Soyer thought it would not take much to put them right. But, on inspecting the Sanitorium Hospital, they discovered the kitchen was outside with no roof and was made out of the mud. He was simply appalled at this condition that the wounded had to suffer and was determined to make it right. By mid-may, Alexis was getting frustrated his stoves had not arrived and the rebuilding he asked for was going very slow.

Soyer meeting Mary Seacole

It was around this time he met Mary Seacole, their encounter is told in Soyer’s ‘Culinary Campaign’ and ‘Wonderful Adventure of Mary Seacole in Many Lands. By June still frustrated about the lack of rebuilding and the none arrival of his stoves, started to tour the many different regiments and see their cooking facilities. He quickly decided that each regiment should have a trained cook, armed with his book about simple receipts. Which he had quickly written. He started straight away by getting the small team of cooks he brought to the Crimea with him start teaching selected soldiers to cook. The Army loved this idea and exploited it. This gave rise to the Regimental cook and to the Army Catering Corps, which is now today part of the Logistic Regiment. Today their HQ is called Soyer’s House and each new trainee is taught about Alexis Soyer.

Florence Nightingale 1881

Although the diets and receipts Alexis had suggested that the army was being used and the rebuilding was undergoing and trying to complete Alexis’ designs. The government were finding William Russell’s Constant reports from the Crimea, troublesome and irritating, they even tried to censor the Times newspaper, to no avail. One of Russell’s reports how superior the French, Turkish and Sardinian army was to The British army in terms of condition, kit and stores. This caused a great debate in Parliament. In a Times leader published on 4th August 1855, it was reported how the government was going to give another £2,568,335 to the Commissariat service of the Crimea, which was “the department that gave chief embarrassments”. The government – because of Alexis Soyer – accepted the fact that it was very unfair. “Imposing a vast amount of labour on men already overworked by fighting was a fatal impediment to anything like wholesome cookery.” The leader continued to report that Mr Robert Peel in speaking to The House of Commons praised the work of M. Soyer saying that; “the services of that accomplished artist had been effectively applied to the improvement of the military kitchen”. And the Times leader hoped that “with the continuing instructions of M. Soyer, the lot of the British soldier would improve”.

Whilst visiting hospitals Alexis Soyer and Florence Nightingale was approached by a French doctor Dr Pincoff asking if they would like to visit the French Great Hospital. Which they accepted, both were very impressed [I mention this as it was from this hospital that Nightingale got the idea from rising patients at 6 am, and the Nightingale wards]. Alexis did not offer his receipts or invalid diets as the French only believed in giving their patients a thin soup.

On the 27th August 1855, Alexis put on a great display of cooking with his stoves. Disappointingly for Alexis, only his large stoves had been delivered which he had designed for placing in kitchens. The smaller stoves were yet to arrive. However, using a soldiers food rations Alexis and his team cooked all day, the afternoon there were several hundred people in attendance, including General’s Simpson and Pelissier. They were very impressed and wrote letters saying so. The relationship between Soyer and Nightingale was quite fraught. Nightingale did not show gratitude, as many attested to later. In reality, she expected to be in charge of the hospital, their kitchens and diets. The fact that the government had asked the same of Alexis put her nose out the joint, to say the least on 19th October 1855 she wrote a letter to her aunt writing ‘I hear Soyer is called a Humburg, because he leaves the work half done and goes on to something else, while that goes to ruin, which is true. Nightingale had no idea the problems Alexis was having with the Crimea quartermaster in getting a constant stream of supplies. Neither was she bothered when writing this Alexis had taken to his bed, with Crimea fever and stayed there for 10 days. Yet when she was ill Alexis nursed her back to health Her remarks were unworthy of her, but not surprising. After the war, Nightingale who had kept meticulous records of wounded and deaths in all hospitals wanted to publish them. When Lord Panmure saw these figures, he would not allow the publication of them and declared them Papers of State. His reason was that her figures showed her hospital –Barrack Hospital – had the worst death rates out of all the hospitals, which would not help her reputation. In fact, they would have probably destroyed her reputation. These figures only came to light in 1998. But, putting aside any challenge to the Nightingale myth, they still give a good insight into the deaths at Crimea.

Florence Nightingale Carriage, that she abandoned in the Crimea but Alexis found it and returned to England at his own expense

When the war was over, Alexis stayed behind touring countries, learning about the ingredients they used in their cooking. Whilst he was travelling the government had decided to pay all Alexis’ expenses and staff wages, and on top of that to pay him a wage, which was equivalent to a Brigadier General’s wage. So, on learning that Alexis was well pleased.

What people had not realised that Fanny Cerrito was touring Russia and Alexis was waiting until she finished so that they could travel back to France together and spend some time together.

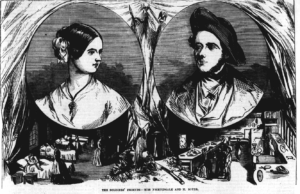

The Soldier’s Friends. Pictorial Weekly Newspaper 30th June 1855.

Footnote: Alexis smaller Field Stoves arrived in the Crimea after the fighting had finished. The army was still impressed with them and Alexis gave the patent to them to the Army.

Francesca (Fanny) Cerrito. Fanny, as she was more popularly known, started her affair with Alexis in...

Another Soyer who was considered the best chef in the world in his time, and claimed he was the gran...

For those that are interested in the correct dates of people surrounding Alexis Soyer and his immedi...

Emma Jones was born in London in 1813, and was instructed in French, Italian, and music. At a very e...

This post will introduce you to Alexis Soyer's books, his various sauces and beverages and to some o...

Soup kitchens The great hunger. There had been Famines before it and Famines after it. Withou...

This is a post about Alexis during the year 1850, including his invention Soyer's Magic Stove....

One of Alexis Soyer's major challenges, his Soyer's Universal Symposium which he set up in 1851 to c...

This is to introduce the reader to a man that made Alexis life miserable in his last 8 years of life...